The Mystique Of Wind - Part 1

It’s fair to say that science and fiction have long intertwined. This fertile coupling in our minds has fathered one after another trope, meme, theme, leit motif. As with dragons, aliens, Atlantis and UFOs, it has never been easy to dissuade devotees of their allure. Such is the spin of wind power in high producing states like Texas.

Whether the allure is inspired by economic gain or by the perception of inherent goodness, is hard to tell. What is evident at least compared to Europe and Scandinavia, is that in the U.S. government incentives have not kept pace with foreign momentum nor with Americans’ wishful thinking.

So seductive is the promise of generating electricity from wind, that the realities are easily glossed over. Yet the juncture of wind’s intermittent nature and the power grid signal one of the main jumping off points for the cleantech renaissance already underway.

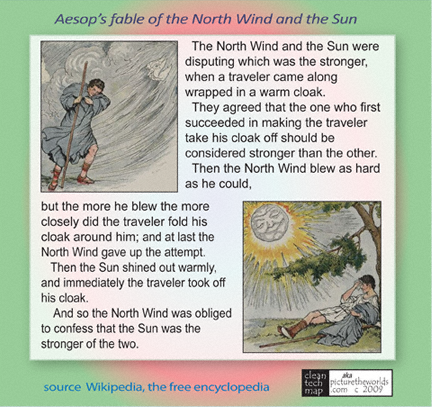

As in the Aesop fable from long ago made its way into Nora Ephron's 1996 script when John Travolta as the archangel Michael quotes while staring out at three hay bales on a harvested field somewhere in the midwest and recites the parable of the North Wind and the Sun.

The point is that our common stories of the past tell us that the wind mystique began long ago, when we intrinsically understood our dependence on energy to grow our crops and sail our ships, before it was commoditizied as renewable. This blog is Part 1 of a series that explores the tendency to overlook the complexity behind the talking points used to describe the benefits of renewable energy.

Media reporting, public discourse and political rhetoric tend to embrace the number of turbines, wind farm acreage and installed megawatts by skipping over energy basics. Let’s take an arbitrary example of an Associated Press story that ran in the Austin American Statesman in early October. According to operator E.ON Climate & Renewables North America, Roscoe (Texas) Wind Complex, “the world’s largest wind farm got up and running…[at]…full capacity of 781.5 megawatts.” But what exactly do the numbers used to describe energy capacity tell us?

Historically, it has been popular for reports about renewable energy to re-state the number of megawatts a facility produces in an equivalent number of homes that could be powered. According to the Roscoe news story, 781.5 MW would power 230,000 homes. However, until we grasp the relationship between wind farm power production and residential consumption, it's hard to fathom that the efficacy of wind towers, much like the variation of people and climates nearby, come in just as many temperments as temperatures.

This starts with the plethora of appliances and electronic devices that fill up our time and make it no longer credible to presume that one megawatt of electricity can support 1,000 homes. This once common notion has paled for an even less obvious reason than our energy hungry plasma screens. By regularly leaving out the point that energy usage varies by regional climate, population, income and single vs multiple-unit houseing, media coverage gives the impression that one turbine is much like another no matter where it spins. The reality is far different.

In fact, in the northwest and northeast of the U.S., households consume up to one-third less energy than in the south where warmer climates lead to increased energy usage. A chief culprit is more months and lower settings for air-conditioning. In contrast, the west coast has stricter environmental laws and building codes which lower energy usage. The average 2007 monthly household consumption in Maine, for example, was 530 kWh compared to 1,276 kWh in Louisiana.

While bigger numbers may not necessarily bestow bragging rights when it comes to energy, the mystique of wind behooves not just policymakers, but all of us to take a more realistic look at our renewable energy assumptions.

We can begin by finding out the total residential load or how much electricity 230,000 Texas homes use on average in a year. (On its website, the U.S. Energy Information Administration shows the average 2007 annual Texas household consumption of electricity was 1,136 kWh per month. Multiplying 1,136 by 12 months = 13,632 kWh per year per home on average. Dividing by 1,000 and rounding up 13.6 gives us the 14 megawatt hours.) Multiplying 14 MWh per household by the 230,000 homes Roscoe wind turbines are said to ‘be able to’ serve works out to a total of 3.2 million MWhs that would be needed based on 2007 usage.

The next step is to calculate the maximum amount of generation that could be produced from the 567 Roscoe generators in a year. Here we start by assuming the generators will operate at their rated capability (781.5 MW) during all hours of a year (8760 hours) which muliplies out to 6.8 million MWhs. In other words, if the Roscoe generators operated at a 100 percent capacity factor they would generate 6.8 million MWhs in a year.

Dividing the 3.2 million MWhs of total estimated generation production the Roscoe homes would need annually by the 6.8 million MWhs of maximum potential generation the turbines could produce in a year shows the Roscoe farm operating at a capacity factor of .47 or 47 percent. This number seems optimistic since wind power facilities currently have closer to a 30 to 40 percent capacity factor.

Taking the midpoint, 35% capacity (35% x 6.8 million) comes to 2.4 million MWhs. When divided by 14 MWh per household, this equates to 185,000 homes or 45,000 less homes than claimed in the article, representing roughly a 20% overstatement. The theoretical capacity is but one of the many theoretical 'facts' surrounding renewable energy that when strung together never quite dispell the mystique.

Part 2 of Mystique of Wind relates the characteristics of wind that matter in the design of clean technology. The last part of the Wind Mystique sequence will look at how the economic and policy road map being planned influences the growth of the cleantech sector.